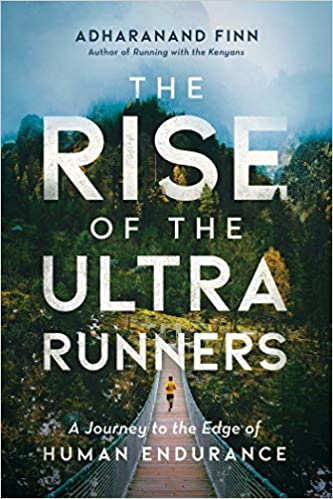

THE RISE OF THE ULTRA RUNNERS

By Adharanand Finn

272 pp. Pegasus Books. $16.75.

It’s my humble opinion, author Adharanand Finn leads an enviable life. The cover jacket (see above) of his third foray into the running genre gives off a powerful, influencing vibe. For me, it carries sway like a Star Wars movie theater poster. Part research mission, part memoir, all engrossing, Finn’s latest push deviates from the path of his past works (ie, associating a region, or culture, and it’s relationship with running). For example, “Running with the Kenyans”. Instead, “The Rise Of The Ultra Runners” focuses on a particular running subdivision, or classification. It’s about the dedicated people that run incredibly long lengths, and what makes them tick. Of course, he’s commissioned to do it, and receives substantial backing from his wife and family. Enviable, indeed.

Finn’s now well established his methodology for aggregating the details of his works. Basically, he declares himself the preverbal experimental lab rat, putting his quite capable running prowess to the test against the matter at hand. Here, that’s running super far, super fast. He intends to race the Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc (UTMB) mountain ultramarathon, giving some purpose to his pending travails. Notably, one doesn’t just register for the UTMB. It’s required to gain enough race points through qualifying trail races over the previous two-year period. So, on goes Finn, racing the likes of (but not limited to) the Oman Desert Marathon (165km), the San Francisco based Miwok 100k, and the “100 Miles Sud de France” in the Pyrenees. That said, a couple other experiences more so piqued my interest: South Africa’s Comrades Marathon and the 24-hour Sri Chinmoy Self-Transcendence 24-hour Track Race in London’s Tooting district. Accordingly, therein I expand.

The world’s oldest and largest ultramarathon, Finn champions Comrades race history (it was a WWI veteran’s idea for rekindling the grand physical achievements of war time experiences). Starting in 1921, in more recent decades it’s also served as a uniting force for South Africans, boosting what participants have in common, and in doing so, at least temporarily, shelving that country’s past racial tensions. A host of medals are dangled for race finishers. Among them the “Wally Heyward” medal for completing it’s 90km distance in < 6 hours, but finishing outside the top 10 (understandably, making it a rare medal), and the “Bill Rowan” medal for < 9 hours. While racing, Finn entertains with a group (ie, the “bus”) experience, shepherded by a pace lead (ie, the “driver”), who nearly, metaphorically, kicks a passenger off. Also, the heart breaking nature of the race’s 12 hour cut off is successfully transferred. Try comprehending running since dawn, yet not fast enough, and being only meters away. Close enough to watch the officials turn off the lights. It’s a tragedy.

Finn’s Tooting-based 24-hour Track Race starts simply enough. The plan is to run for 25 minutes, then walk for 5 minutes, and make silly faces at the wife throughout the entire track-based run. Reality settles in approximately halfway through the race. Increasing body aches and burning sensations has Finn contemplating quitting. Further, the race offered no UTMB race points, rendering it arguably meaningless. Hours grind on, as does Finn, but with burgeoning focus on the agony of it all. Also, debuting a new pair of shoes at the race wasn’t terribly wise. Finn’s a pro. Mention of it’s happening seems silly. However, credit him for admitting it. Every runner has the occasional silly lapse. Next, Finn declares his body broken. Kaput. The effort’s gone futile. You get the idea. Yet, he ambles on. Then, one foot in front of the other, turns into more of a hustle. His feet start responding better to jogging than walking. He generalizes this experience in revival as moving from darkness to light, referring to it as “self-transcendence”. In the end, there’s 13 DNFs and Finn’s 28 out of 32 finishers. How many miles did he run? Read “The Rise Of The Ultra Runners” to find out!

Constructive criticism? The book can be a bit scattered. While Finn’s intent is to provide the reader an ultra running education, his methods can be all over the board. To be fair, the subject’s scope is huge, and Finn perhaps intended to harness it all with his UTMB drive. Still, my suggestion being, is delivering ultra running matters as it relates to so very many physiological disciplines, racing on a worldly scale, and highlighting his personal and professional happenings as it relates to the genre, just too broadly focused?

🏃♂️📚

#DidYouKnow courtesy “The Rise Of The Ultra Runners”: At least one famous race monitors the progress of it’s participants via means of stealth? A portion of Finn’s book is dedicated to discussing cheats in the ultra world. Interestingly, the Comrades Marathon deploys undisclosed timing mats to ferret out “… the multitude of people who try to claim that they completed the famous race when instead they hopped in a car…”.

#Follow Adharanand Finn Here